Michael Balderstone of the Nimbin Museum explained that ATSIC, (Aboriginal and Torres Straits Islanders Commission) was too mean to allow Aboriginal people petrol money to visit the Timbarra Plateau. They would show Ross Mining the sacred site to be spared by their proposed open cut cyanide gold mine, on wetlands, sourcing the Clarence River!

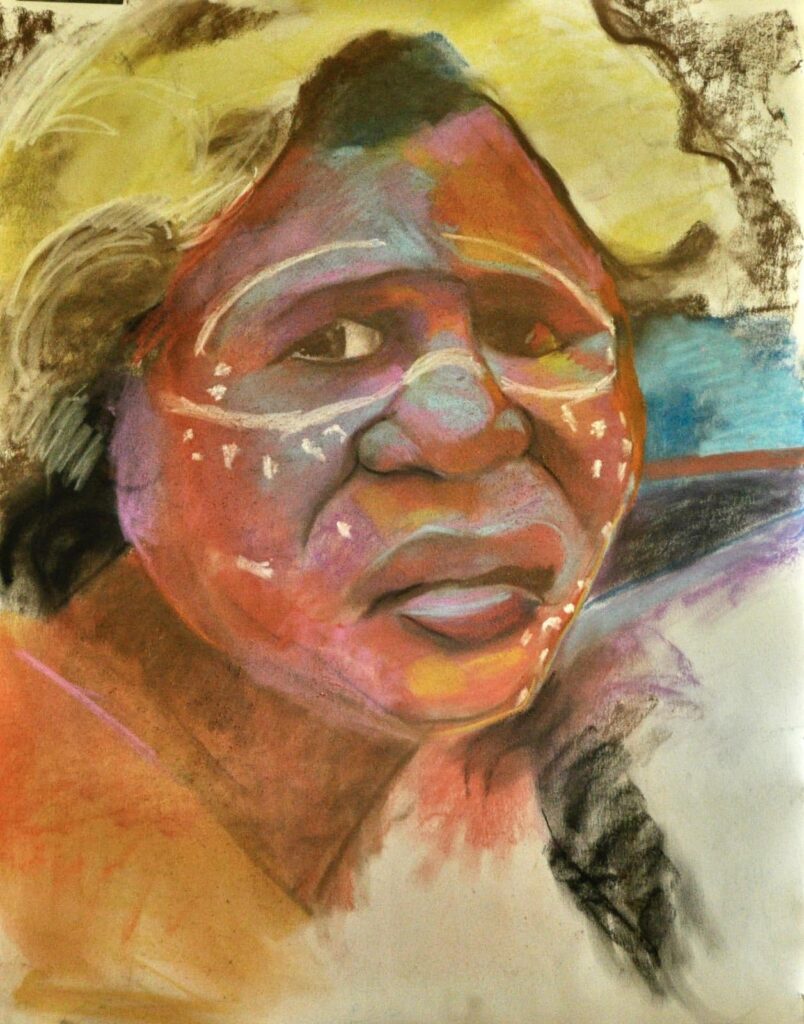

Delighted, I drove Burri Jerome in my four-wheel-drive, out to the Tabulam Mission. Burri’s childhood in the Kempsey Mission was beset by both demoralised drunken elders, and by racist white rednecks.

At the East Sydney Tech, he became a good artist, then media representative during the Redfern riots, but was not accepted as, ‘one of our mob’, by the local Bundjalung mobs around Nimbin and Tabulam.

At Tabulam we met the elder, Uncle Eric Walker, then old and frail, and several others for the outing. Leaving the highway, we took a narrow bush track of two sandy wheel ruts threading magical forests. The bush was unspoilt and enchanting its ecology undisturbed. The day was sunny and warm.

Soon the miners arrived in their ute, Uncle Eric withdrew a little and leaning forward, intoned an incantation, gesturing with his hands. The sky went dark. A dense black cloud condensed overhead and pelted us, savagely with hailstones. Taking fright, the miners hid under their vehicle. Ten minutes later, the storm ended. The sun shone out once more. Burri’s footage of the day has, of course, been lost.

Uncle Eric pointed to huge granite tors on the skyline, the climax of an ancient men’s initiation cycle, lasting months, beginning on what is now Queensland’s Gold Coast, walking south along the Bundjalung seaboard to today’s Grafton, then turning inland and climbing to this sacred site. For me, it was, ‘love at first sight’. I would oppose the mine.

Not a twig of this pristine flora should be broken, but gold mining was the founding ethic of our nation and governments of either stripe need gold production to boost their coffers and maintain their Triple-A credit rating with Moody and Poors, S&P, or Fitch, so that they can borrow for public works, at lower interest rates.

Bob Carr’s Labor government strongly supported the mine despite opposition from five government departments, including the National Parks and Wildlife Service, rating the Timbarra plateau of “outstanding and unique conservation value”. Its complex of ecosystems ranges from damp sedgelands through dry heath forest to warm temperate rainforest.

The composite ecology of the plateau is subject to northern sub-tropical, eastern coastal, western desert, and cool southern climatic influences. Ignorant of what better to do, I made posters of fauna and flora menaced by the mine. At local markets, I spread the posters. The public was slightly curious about these creatures and this issue, so far from its world.

Timbarra is home to endangered and threatened species including the Hastings River mouse, brush-tailed rock wallaby, stuttering frog, glossy black cockatoo, sooty owl, tiger quoll, and parma wallaby, and five flora species of conservation significance. The mine turned the innocent bush track into a wide clearing with cambered clay and gravel road, power lines and poles.

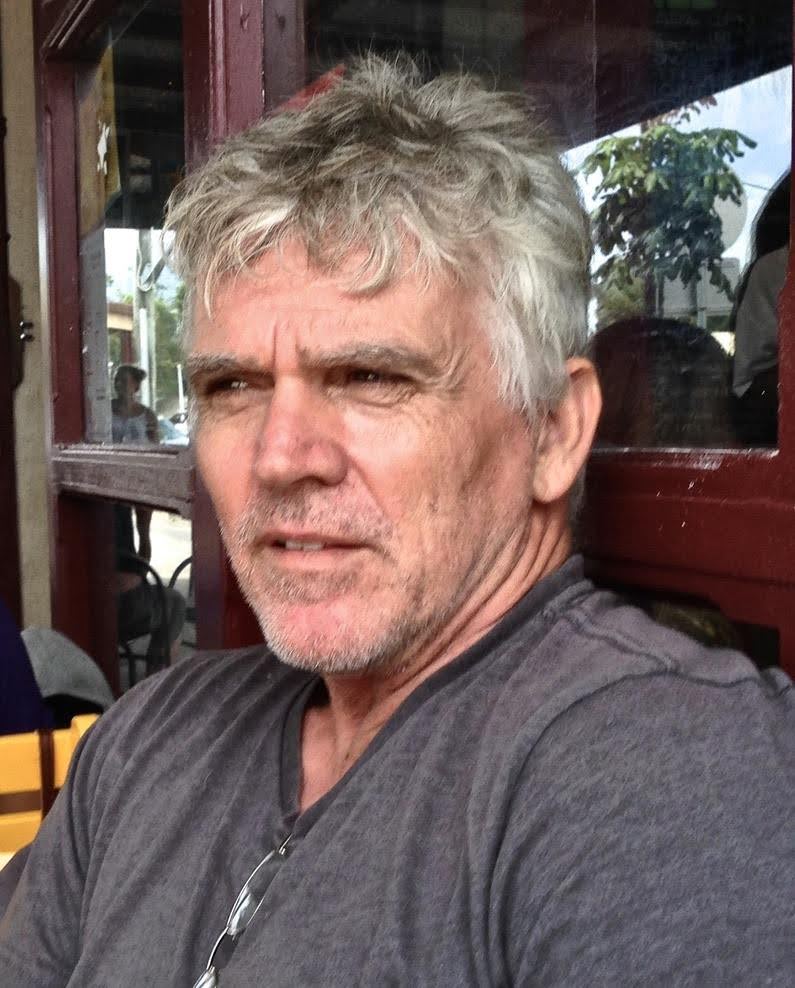

Back then, over thirty years ago, in 1993, Al Oshlak, our veteran local activist, was just beginning his career in court, where I have watched this successful bush lawyer, now of the Indigenous Justice Advocacy Network, pleading environmental cases, arguing slowly and carefully as a lay advocate, taken seriously by the bench.

David Heilpern, sub-dean of Law at Southern Cross University, wore a white T-shirt embroidered in red capitals, ‘LEGAL OBSERVER’. I watched Police obeying his directions. Any activists in trouble with the law had David’s advice and skilful protection, often arguing that the alleged incident was actually not on the gazetted road as the prosecution claimed. As a layer of legal protection, he advised that our written material should be in the name of the Timbarra Protection Coalition (TPC).

He advised me to join the TPC. Six or eight of us met each week around a mull bowl, to discuss tactics. I was a stranger among them. As a newbie, I had not been a member of the inner circle, the North-East Forest Alliance, or NEFA, with a grand history of the first ever rain forest blockade, at Terania Creek, a famous victory, spreading globally.

Graeme Dunstan tells how, ‘we felt powerless before the bulldozers until we joined hands and began singing. Then we were powerful and stopped the monster.’

Some suspected I was a spy for the Australian Security and Intelligence Organisation, or ASIO. Some threatened violence. What a slap in the face for one turning his life from attending urban distress, in a respectable profession, to eco-activism! Michael encouraged me to, ‘Just hang in there!’

As eco-activists, we were non-violent, in the lineage of Gandhi and Tolstoy who had inspired him. Meanwhile, Michael asked Konrad Jankowski to be my minder if things got rough, whether by the miners we were opposing, or by activists, some very angry at my unwitting intrusion contrary to secret deals between politicians to sacrifice Timbarra.

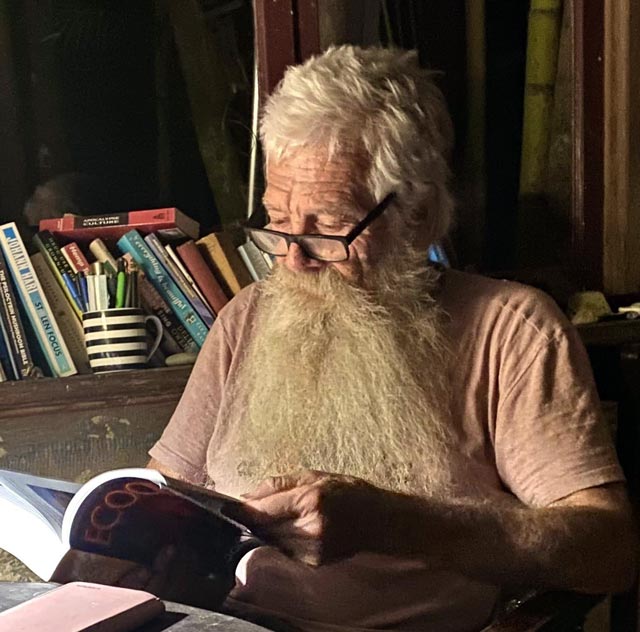

Konrad and I had happy times on reconnaissance of the plateau, walking and camping in sublime surroundings. Konrad, now a good friend, was an experienced activist, if a bit too ready to ply his fists. He had done time on four occasions for assault. Each time, for honourably restraining police officers, so that his friends could escape arrest.

Once in jail, Konrad refused the ‘hard labour’ to which he was sentenced. Given solitary confinement, Konrad declared, “I loved it! . . . They gave me reduced rations, just water, potatoes and dry bread. . . . Through the bars of my cell, I threw half of my reduced rations out onto the yard below. . . . The screws came to respect me. They did me favours.’

Activist lore told of Myles Dunphy OBE (1891–1985) who, in 1910, helped establish the wilderness movement, and later the National Parks service. Myles’s son, Milo Dunphy AM (1928-1996) helped to double the area of National Parks in New South Wales. He stood as an independent in Bennelong against the future prime minister, John Howard.

On his deathbed, Milo made premier Bob Carr promise he would never mine Timbarra or Lake Cowal, but the parliamentary Greens had since done a secret deal to sacrifice Timbarra in exchange for Lake Cowal, The Overflow of Banjo Patterson’s Clancy. Both sites are now mined, with the Labor government strongly supporting the mines.

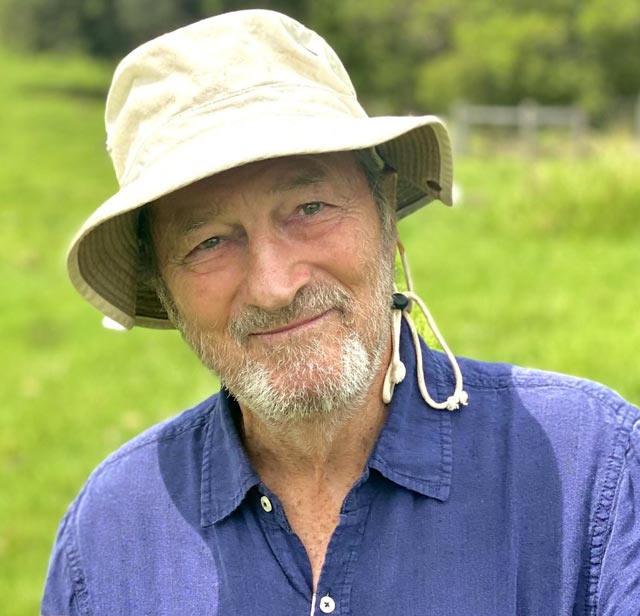

A long-time local, Peter Hardwick, an experienced activist raised in several parishes of the Clarence valley, became my friend and co-worker, advising on tactics. We argued over every word and comma in the letters we drafted for politicians and the media. An autodidact, Pete taught me heaps.

We discovered the power of print: once it’s on paper, then, in default, those responsible are, liable to prosecution. New crimes of Ecocide are proposed, to be tried in the International Court in The Hague. Shareholders in any guilty industry would be responsible for their investments and liable to prosecution. What a stroke for the Earth!

In a marquee at Tabulam, the miner fulfilled its statutory duty to negotiate with Aboriginal people: explaining that they would quarry and crush the sacred mountain to twenty-cent sized pieces. They would ‘build the crushed granite into new landforms’, or leach heaps on sloping ground covered with plastic membranes – known to leak.

Black Polypipe and sprinklers would spray the heaps with lethal cyanide. Trickling down through the heaps, the cyanide would leach or dissolve any traces of gold out of the crushed granite, to be collected on the plastic membranes below, draining into a ‘pregnant pond’. Then pumped through towers of iron filings the gold precipitated.

At question time, Regional Manager of the Environment Protection Authority (EPA) Simon Smith, admitted that the plastic membranes always leak, so cyanide would seep into surrounding wetlands sourcing the Clarence. Effectively, the EPA’s function is to authorise environmental destruction. Aboriginal people present were speechless.

Favouring one Aboriginal family over others, with flattery, expensive restaurants, five-star motels, and flights in chartered aircraft, the miner played one off against another, in their well-honed cynical manipulation aimed at indigenous assent to the mine. To persuade other Aboriginal families, the miner filmed Uncle Eric receiving an ingot of gold and putting it in his pocket – till the frail old man realised he’d been set up.

From the mine site, Nelson Creek tumbles down from the plateau to join the Rocky River, which becomes the Clarence further downstream. In its secluded gully lives a deep-sea diver and underwater welder, Peter Pumpkin (Stanford) retired from oil rigs. With his mountain stream endangered, Pete, in military camo, joined our campaign, raising morale and offering his creek flats as a base camp for many activists.

We were already having the best fun, blockading the miners. We dug deep pits in Her Majesty’s Road, filled the bottom with concrete embedding a steel loop. Courageous young activists lent down the pit, locking their wrist to the steel loop. Their bodies lying on the road prevented any vehicle from passing. Poor constables did the hard labour digging them out.

Activists raised saplings into tall tripods on the road. An activist sat in the fork above, their life at risk if police dared move the tripod. Driving 200 km to hire a cherry picker to reach and arrest the protester, returning police were outwitted when several tripods with a horizontal sapling between their peaks had the activists escaping arrest by moving between the tripod tops.

But NEFA remained aloof. Then we heard that a law student, Sue Higginson, a greatly respected passionate environmentalist, was interested. If Sue joined us, the NEFA mob would come with her. An activist had locked his neck to the bucket of a big yellow excavator. ‘I’ll rip ‘is fuck’n head off’, yelled the operator, revving the engine.

‘No you will not’, retorted Sue. “You’ll turn the ignition off, she commanded. You’ll do it now! . . . Do it now!’. The poor man obeyed. Along with Sue, now in the New South Wales upper house, came Johnno Williams an intrepid eco-warrior renowned for his experience, good judgement and daring – fair bloody legend mate! Then our numbers exploded.

Eighty protesters from Lismore, Canberra, Melbourne and Sydney, from Friends of the Earth, the National Union of Students, Southern Cross University Students Representative Council, Timbarra Direct Action Group, Graeme Dunstan’s Peace Bus, Resistance, and local conservationists and residents got involved.

On June 7, 1999, Police harassed activists taking non-violent direct action, sampling water for analysis of cyanide. More than a hundred protesters blocked the road into the mine. Police panicked at the size of the protest, and reacted violently, arresting twelve protesters.

For humans, the lethal dose of cyanide is one gram. To extract 50,000 ounces of gold, worth $ 20 million, Ross Mining admitted intending to use 700 tonnes of cyanide annually, 75 tonnes of caustic soda, and 60 tonnes of hydrochloric acid. This chemical engineering would threaten the region on high altitude fragile wetlands feeding the Clarence River. Poor frogs!

Just as Britain, during the Industrial Revolution, promoted gin to pacify its workers, and as Britain had pressed opium on the Chinese to weaken their resistance to British trade, there were rumours in our camp that the miners were supplying heroin to our members to cripple their resolve.

After a TPC meeting in Lismore, a new pretty face with big dark eyes, asked me for a lift back to Nimbin. On the way she asked, ‘Would you like a taste of smack’. “I reckon I’d vomit’, I replied. ‘Not always’, she pleaded. ‘I’d get addicted’, I parried. “Not from only one hit”, she murmured. ‘Let’s wait till we’ve won this campaign.’ I said.

Leaving, she pleaded, Do come in and try. I saw her never again. I used to say, I’ll try heroin in my eighties, but midway, I’ve done nothing about it – not yet. In a local paper the miner published fake news that I was preying on young women involved, but the women said, ‘John’s not like that!’ Embarrassing either way, the libel died for lack of legs.

At the Gold Miners’ Annual Conference at Jupiter’s Casino, Broadbeach, on the Gold Coast, we infiltrated the audience, planning to seize the microphone denounce gold mining and disrupt the meeting. Noting our hippies’ strange dress, security guards ushered us out. On the lawn outside, we filmed our group with banners and placards, sent footage to a TV station, and watched it on the evening news.

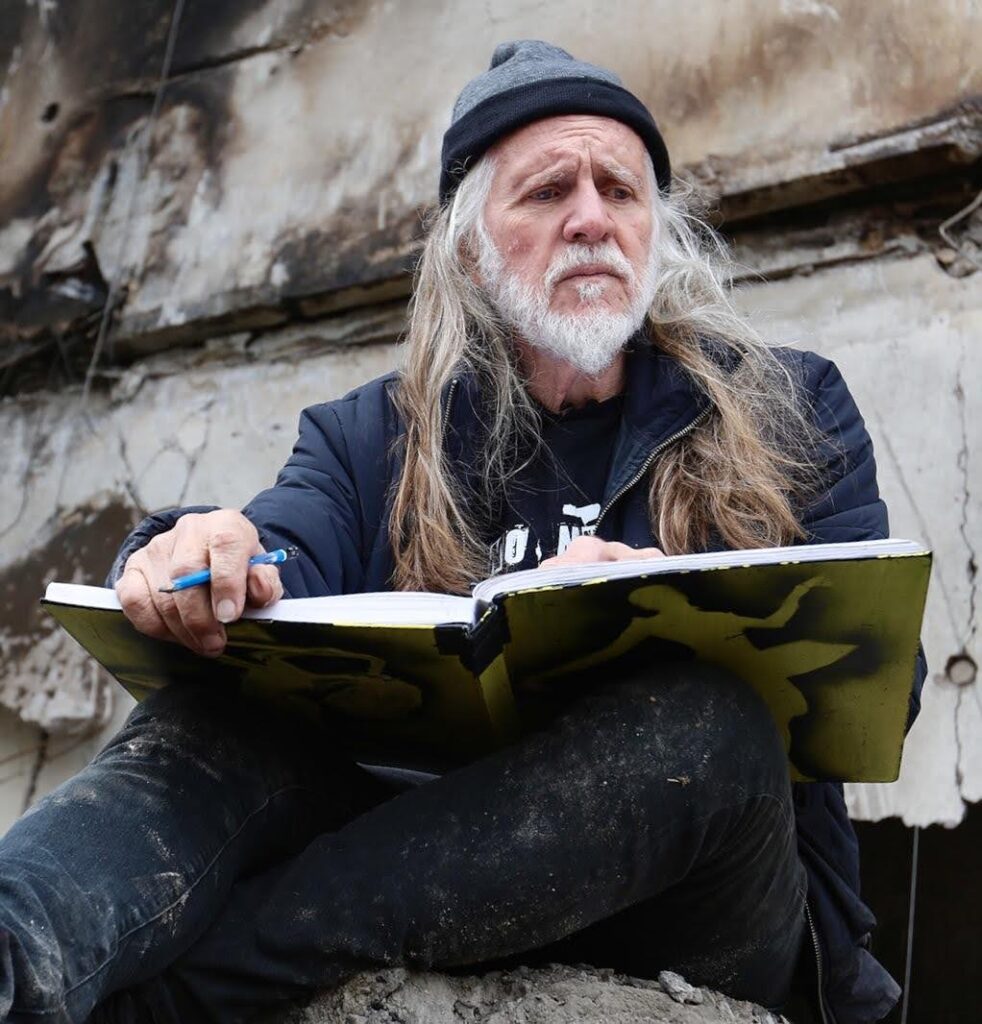

Up from Sydney, Ian Reid brought Michael Ramage QC, and Australia’s official war artist, George Gittoes, who said it was like any battlefield: chaotic and uncertain, for example, a confrontation between protesters and a miner operating a machine was about to cause injury, when Graeme Dunstan leapt in and pulled the plug on the machine.

Bill Petrie had a grazing lease on the plateau. The protest climaxed after his wife, Bronwyn, invited many grazier friends to come and deal with us ferals in the practical way that landed gentry enjoy most. Bronwyn’s mob arrived in utes, with firearms and Eskies full of beer. Police had to quickly switch roles from opposing us to protecting us.

To prevent encounters, police felled a tree across the road and mounted a guard between opposing camps. A bushfire was baring down on us. Our blockade had blossomed into effective protest.

Then, at the Tenterfield Annual Show, with passions inflamed, We would boldly show my posters. ‘We’ll be front-liners’, warned Konrad. Anticipating violence, police begged us to leave, but we stayed. No violence occurred.

Uncle Eric asked Burri to stop the mine and save the land. Burri forsook his painting and joined Al Oshlak and Spook, driving overnight to Sydney for court cases lasting months. His court drawings were lost to fire with the Nimbin Museum.

The late Barry Hudson had a mystical experience of Aboriginal identity with country, changed his name to Murri and with Johnnie Chai, served tea, and coffee to activists at their Nimbin basecamp, behind the museum. Thousands of popular ‘cookies’ were sold – a big campaign fund raiser.

Timbarra taught me that it’s hopeless appealing in law to a code written for environmental exploitation and destruction. The time is past for single issues: “Not in my backyard” no longer qualifies. Our ecocidal culture, due for radical review, but codified in law, defends our ecocidal behaviour. It goes back to our most human-centred religion

Christianity has survived so long because it works for humanity. It works for humanity because it is human centred. Of all known religions, it is by far the most human centred. Its human-centredness, however, is at the cost of other species. That cost is now becoming critical to the survival of our own species.