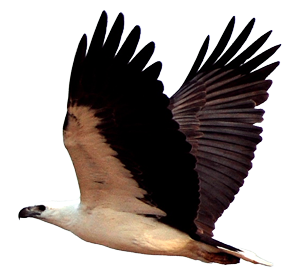

Walking cliff tops facing the Indian Ocean north of Broome, I halt in wonder at fireworks in the sky, an osprey going ballistic in my face. Bright sunlight on white underparts flashes alarm! And lo, on a jagged buttress jutting out across the beach from red cliffs, is her nest of many seasons piled high with sticks and flotsam.

Climbing down a chimney in the cliff face, I leave no silhouette against the sky. Slowly she settles, returning to the nest, crouching over her brood. But where is her mate? … He’s off hunting … but he doesn’t return. Waiting, I see two hatchings, their discarded shells and one speckled egg, still unbroken.

Next morning while the nest is in shade below the cliff, I walk far along the beach, swim, dry my face on my shirt and return to menacing aerobatics, now by both parents. Go away! Their wings rebuff me with their psychic draft, but the third chick has hatched. I can see its shell, now broken.

Again in the crevice of the cliff, jamming my knees against its sides like match heads hard against their gritty striker, I am comfortable and in shade till afternoon. Jamming elbows gives steady support for binoculars and camera. With sun behind me, my view of the birds and their nest is perfect.

The view beyond is surreal: In dazzling light, blood red cliffs, topped bright green, fall to beaches, coral pink and apricot, with chocolate rocks. Turquoise, deepening to lapis, the sea, barely rippled glitters like diamonds, its surface broken by pods of whales at play, spouting, breaching; great tails waving and splashing white spray. What a gift, to be here, to be watching this idyllic primal scene! As a child I read of such adventures. As if by accident lifelong dreams have come true.

Seventy years cohere. In a warm glow of consummation, this rock and I are one flesh – as in love. Embracing alien but willing limbs, the innate power of country enters a welcoming brain, answering explicit invocations in this long-sought merging, to which it aspired; deliberately inviting the spirit of the bush to invade the body, via the senses; to inform the mind; doubtless prompting these reflections?

At the edge of the continent, this red rock is a stepping-stone, a threshold, or doorway ajar to a tattered fringe of primeval culture; this cleft a fleeting aperture through which to glimpse – backwards, away from the bright vision into the obscure wisdom of the ancient Dreaming. As my camera’s shutter blinks, light and shade become one.

I will wait as long as it takes to photograph father returning with a fish flashing silver in the sky. But no, on a pinnacle of red rock about fifty yards from the nest, he sits stolidly for hours in morning sun, statuesque, formal, scarcely moving but for his head, ever alert, quick and watchful.

They look an ill-matched pair; he about half her size, younger and dapper; she bigger, older, wilder, tail bedraggled and in a different psychic space; fierce, crazed, distracted and restless, fussing and flapping over the nest, snuggling down over her brood, then leaping into the air; not because of my presence, 100 yards distant, in shade, motionless within the cliff, though they do check me often with huge eyes, glaring yellow. Other osprey nesting in busy public places, are less disturbed. What could be the cause of her agitation?

And so we sit for hours, a triangle of heightened awareness; I furthest, least exposed and so still that gazing on this brilliant scene, I drift into timelessness, entering avian mind, nesting on such sea cliffs from before Gondwanaland days, back through its dinosaur heritage and into the passionate concern of mothers for their offspring.

Eternal peace prevails, when without warning, he flies out of sight around a cliff. Now my moment is coming! But I’m surprised when she flies after him, leaving their hatchlings exposed to hot sun, blue sky and to whatever predator might come. Shortly he returns, straight to the nest, bringing no catch, but crouching low, his back to me. I can’t see the chicks. Then she returns, also without prey.

Turning towards me, he’s eating something pale, hard to discern. She watches closely, their heads together, but she does not eat. Nor do they feed their young. Did he dash back to grab some leftover fish while the missus was away, or had a chick died overnight and he is now making best use of the protein?

Subsequently on my laptop, zooming photos in to pixilation, fails to confirm a hatchling under his claw. But if it was, was its death natural, or had a sibling pecked it? If father killed the chick, I would have witnessed his infanticide.

To any alleged murder, she is accessory, closely attending the cannibalism, though not partaking. Is this a lesson from the wild – a lesson in acceptance, as she hangs her head close beside his, staring at their infant’s corpse, while he tears its flesh apart and eats? Is this a lesson in forgiveness?

Perhaps the pair doubted their chances of supporting five this season and this is a Malthusian lesson in population. Is my arrival a contributing factor? The bright dream has its shadow and with the attraction of opposites, the greater the brilliance around this little death, the darker its shade.

Will she be less alarmed if whitefellas, promising big bucks and jobs, clear 9,000 acres, once unthinkable, along these glowing cliffs for extractive industry, employing 6,000 fly-in-fly-out workers with services to match and other industries to follow? Once custodians, but now assimilating under the stronger spell of a culture whose inordinate power is in the fuel it burns, blackfellas will claim their share of the spoils.

Silver tanks and towers belching fire, smoke and poison vapours, ablaze with lights at night, would process oil and gas piped 600 km from offshore wells, then pump it back seven kilometres along a breakwater of rock, blasted and dumped at James Price Point on a seabed ruined, halfway to the horizon, across migratory paths of breeding whales where dredges would delve and scour continuously for 600 super-tankers each year.

Just another flame lighting the global bonfire of our vanities, this psychic Napalm of our grand insanity sticks to the mind, burning deep; searing the heart, while we scorch and char the planet and its species – not least our own – and our offspring.

John Wilson

Friday, 16 July 2010