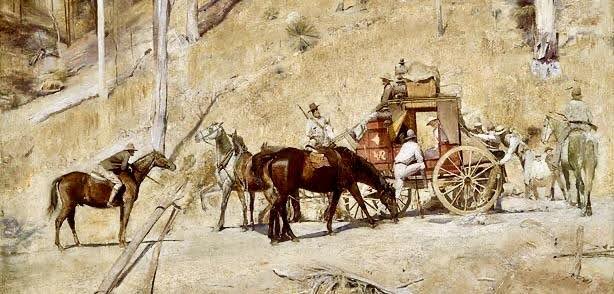

Photo credit: Outback Pioneers

Longreach, May 2024

When I was a child, we didn’t have a motor car. We had a stable with a loft, about four horses and a couple of gigs, jinkers, or traps, like the one in this photo from the web. You can see the step for mounting the gig, just in front of the wheel. Riders had to be both fit and nimble.

At Heidelberg, then on the rural outskirts of Melbourne, there was still a sawmill in the main street with a shrill steam whistle; a coachbuilder; a wheelwright; and beyond a dusty yard with horses tied up in the shade of an old elm, a blacksmith whose hammer and anvil rang sharp and dull across the street. I would swing on the bellows till the black coke in his grim forge burnt white hot.

Mother drove the horse and gig when she went shopping, in the ‘village’ below our house in Castle Street. Every Sunday, after my drawing, or painting lesson, we would fetch the old artist, Clewin Harcourt, from his studio, down by the Yarra River, in The Enchanted Valley, as he called it. We brought him home to our house for Sunday lunch: roast lamb with mint sauce and gravy. Amongst several vegetables the prize were potatoes (par-boiled, rolled in flour then roasted for a superb golden-brown crust) followed by apple pie with custard and cream.

After lunch, we crossed the hall to the sitting room. Before an open fire, we all played in a musical soiree followed by high tea. Then we lit the carriage lamps, fixed them in their brackets and drove the old man home with the dim candlelight flickering on the hickory spokes. In the photo, you can see the lamp glinting through the wheel spokes.

The wheels of our gig, or jinker, had tyres of iron. No prissy rubber tyres for the rough and stony roads of that post-war time. They made a harsh clattering noise, crunching and scraping as they ground smaller pebbles into finer gravel.

To meet visitors from interstate at Essendon airport, we drove our horse and gig the length of a country track between rustic stone fences of basalt boulders, across the Preston paddocks, thick with variegated thistles. That track is now the four lanes of busy urban Bell Street, through densely housed inner suburbs.

On one occasion, mounting a steep rutted bank, one of the gig’s springs broke, bringing the curved wooden mudguard down onto the gravel-laden iron tyre. It made a terrible racket. Our good mare, Merran, took fright and bolted. Mother called to me, ‘Jump for it, John!’ Jumping seemed more dangerous than staying, so I didn’t jump, but held on tight as Mother brought the mare around in a wide circle till she was quiet.

Merran was somewhat deaf, and on another occasion, Mother and my younger sister, Julie, had alighted from the gig when Merran took fright again and bolted down the main street of Heidelberg, capsizing the gig, smashing it to pieces and leaving it as a pile of wreckage outside the old Victorian Post Office, now demolished. Father bought a motor car. Our horse-drawn days ended with my teens.

Hence my wish to feel again the thrill of horses in harness, still occurring only seventy years ago, but now rare. That’s much less than my lifetime, so the speed of change from horse flesh through internal combustion engines, and on to electric vehicles, is bolting like global culture, out of control and prone to disaster. How can we bring it around in a circle until it is calm, or will it end in wreckage?

When last in central Queensland, I was too proud to join the common tourists for a ride in a daggy old Cobb & Co coach, but realising my silly mistake, I drove back 1,200 km to see what it was like in them days, not long ago. They do it well in Longreach: we met in a dusty yard where many horses rested in the shade of overhanging trees, relieving themselves shamelessly in public.

I was lucky enough to be last up, climbing aboard the coach, to sit between the coachman and his assistant, whose job was to jump off the moving coach, to run ahead and open gates, then to close them and run again to catch up with the moving coach, climbing up between the turning wheels onto the box beside me.

We set off through the streets of Longreach and peak-hour motor traffic. What a sight it was looking forward over the backs of four well-fed, well-groomed bays and one black, three leading, two behind, on either side of a central shaft, under an incomprehensible system of long reins, dividing and criss-crossing above shiny backs and magnificent hind quarters!

Out of town, we even followed the old coach road from Longreach, along dusty wheel ruts jolting across savannah, through gidgee scrub, and rattling over stony creek crossings – as of yore.

Our coachman was way cool. ‘I’ve been around horses since before I could walk’, he said – and it showed! He is a real horse-whisperer: barely audible to me, sitting right beside him, he made strange clicking sounds with his tongue and hardly murmured, ‘Steady . . . steady . . . steady’, as the horses, with ears turning, broke into a canter. But coming home he let them gallop.

With the wind on my face, and sixteen aboard a heavy wooden coach, five-in-hand, all galloping in harness, with chains in their tack tinkling and jingling, and twenty steel-shod hooves striking the road in a cacophony of syncopated clatter, was well worth driving a thousand miles to experience! I heartily recommend it! One hasn’t lived till then!

In terms of bodily experience, oh, what we have lost with the relentless onslaught of technology. In this case with automobiles, railways, and airlines, and now, even more calamitously, with the human disaster of the digital revolution, cramming people into conformity with bureaucratic protocols!