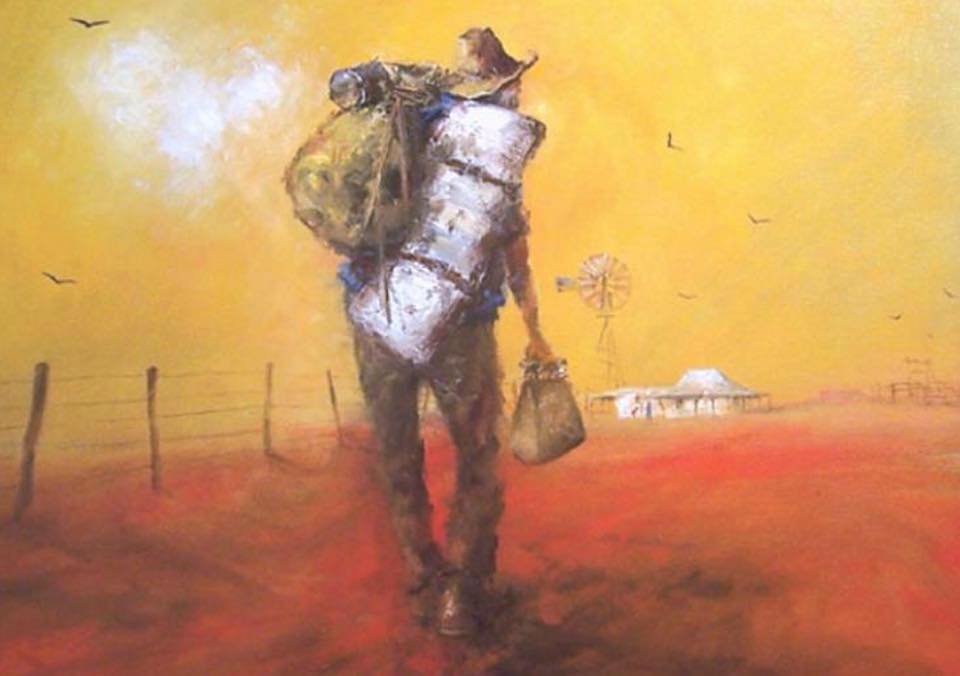

Out of Townsville, over a low ridge, I enter the Lake Eyre Basin of our vast interior. For thousands of miles, I follow smooth clay wheel ruts on old stock routes along the Torrens Creek, the Barcoo, Thompson, Bulloo, Condamine, Paroo and Diamantina Rivers.

Travelling slowly, I memorise for grandchildren ‘The Man from Snowy River’. Camping by shady billabongs I swim, meditate, explore dry creeks, gidgee scrub and open plains, like a wild creature randomly, but with binoculars and GPS to find my truck before dark.

I relish the profound and nurturing silences of the outback, morning and evening choruses, tender sunsets and dawns, filigrees of leaves and branches, the eerie pensive vastness and the patient stars at night. If it’s cold I sometimes have a fire.

Eureka to the Barcoo

At Winton’s ‘North Gregory Hotel’ I shower in bore water. It smells of rotten eggs, but any step to cleanliness approaches godliness. In its turbulent history the hotel burnt down three times, once in the 1890s when a barmaid refused to serve a scab sheerer.

Crossing plains of Mitchell grass (our Pampa) I reach Kynuna. At 200 m. it’s the highest ground between the mountains of Papua and Antarctica. From here rivers, when they do flow go either north to the Gulf of Carpentaria or south into salty lakes of the Red Centre.

On the Diamantina I spend an afternoon with Richard Magoffin OAM, JP, a contentious local whose ancestor Richard Magoffin aged 20 fought under the Eureka flag. Surviving that bloodbath, looking for opals “On the Outer Barcoo” he died in 1885, of thirst.

I had photographed the lonely grave of Magoffin’s Eureka ancestor, two weeks before close to the ruins of the ‘Welford Shanty’, which Banjo Paterson immortalised in 1892, in his poem describing “A Bush Christening”.

“On the outer Barcoo where the churches are few,

And men of religion are scanty,

On a road never crossed ‘cept by folk that are lost,

One Michael Magee had a shanty. … ”

In this poem, Paterson has a “ten-year-old lad” called Patsy, trying to escape baptism by hiding in a hollow log. Mary Durak once told Magoffin that Patsy in Banjo’s poem was in fact her uncle, Patsy Durak, who hid from the visiting priest in an Aboriginal gunya.

His son Richard found the body an hour after death. With three brothers, he moved on to join the first settlers at Kynuna, becoming lifelong friends and marrying Macphersons of Dagworth Station, where the last of the great shearers’ strikes would end, as I shall tell.

The third Richard Magoffin played saxophone to Bob Macpherson’s piano, pumping up “Waltzing Matilda” at Kynuna dances. His son, my informant, now keeps a museum of Paterson and Matilda history for which he got his gong. I have some of his monographs.

Young Paterson

Born near Orange in 1864 Paterson attended Sydney Grammar, but the bank resumed his parents’ property “Illalong” near Yass, preventing his going on to Sydney University with his peers from school. This crystallised Paterson’s left wing political outlook and writing.

Studying law as a clerk, Paterson hated working for banks screwing money out of those who had none. He quotes verbatim Clancy’s mate, who answered Paterson’s letter on behalf of a bank Clancy’s gone to Queensland droving and we don’t know where he are.

Graduating in law from the University of Sydney, Paterson had contempt for idle squatters, for absentee landlords, particularly the English. In 1889 he published a political pamphlet on land reform, forewarning that workers here will soon rebel.

His first poem published in 1885 attacked military leaders recruiting for the Sudan War. Paterson’s politics are also clear in his only other published song, “A Bushman’s Song” of 1892, which excited me in my staid, unconscious and apolitical childhood:

“I asked a cove for shearin’ once along the Marthaguy:

“We shear non-union, here”, says he, “I call it scab”, says I.

I looked along the shearin’ floor before I turned to go –

There were eight or ten dashed Chinamen a-shearin’ in a row.

It was shift, boys, shift, for there wasn’t the slightest doubt

It was time to make a shift with the leprosy about.

So I saddled up my horses, and I whistled to my dog,

And I left this scabby station at the old jig-jog.”

A passionate horseman, Paterson published early poems under the name Banjo, taken from his childhood mount, a family station horse, a Timor pony, suggesting “The Man from Snowy River”, is Banjo writing about himself, if not about his ideal man.

Clive James and Peter Porter hail “The Man” as Australia’s greatest poem. In it Paterson extols youthful ideals of pluck courage bravado and pride. In Clancy he envies the freewheeling life. But, to Magoffin, “Waltzing Matilda”, is a rousing political allegory.

Paterson often helped his mate the unstable alcoholic radical Henry Lawson with legal matters like fair pay and when Lawson skipped the Queensland jurisdiction just one hop ahead of charges of sedition for his revolutionary writings in “Freedom on the Wallaby”.

Socialist solicitor AB Paterson visited ‘Dagworth Station’ six times from Sydney during the four years of the great shearers’ strikes, staying with the manager and part-owner Bob MacPherson until late in August 1894, the year Tom Roberts painted his ‘Golden Fleece’.

Dagworth

Dagworth Station, established in 1873 near Kynuna took the name of a four year old bay stallion, which ran third in The Melbourne Cup of 1872. By 1895 ‘Dagworth’ had half a million acres, 450 thoroughbreds, 150,000 sheep, 300 cattle and owed banks ₤100,000.

Artesian water discovered in the 1890s promised limitless wealth for all. Queensland was booming with vast land holdings heavily stocked, so the banks owned a third of the colony, but itinerant shearers humping their swags and sleeping out rough, got little.

The Great Shearers’ Strikes from 1891 to 1894 had 2,000 angry shearers camped at Barcaldine where a red gum in the main street, The Wisdom Tree lent shade alternately to Salvation Army meetings and to the founding meetings of the Australian Labor Party.

But itinerant labourers still had no vote. Fire was their way of expressing understandable desperation. They burnt down woolsheds as big as cathedrals. Two hundred and eighty police brought in settled most of the strife – except for the final “Battle of Dagworth”.

Seven shearing sheds had already burnt down. Then a paddle steamer ‘The Rodney’ on the Darling was torched by a mob from Sydney possibly led by Henry Lawson. Denying involvement local unionists said the leader was known for running when things got hot.

Bitterness between landholders and shearers persisted. Striking shearers, swagmen, hoboes, cattle duffers and sheep stealers were common in the area. In 1894 The Shearers’ Strike started at Kynuna in April and spread to all the eastern colonies.

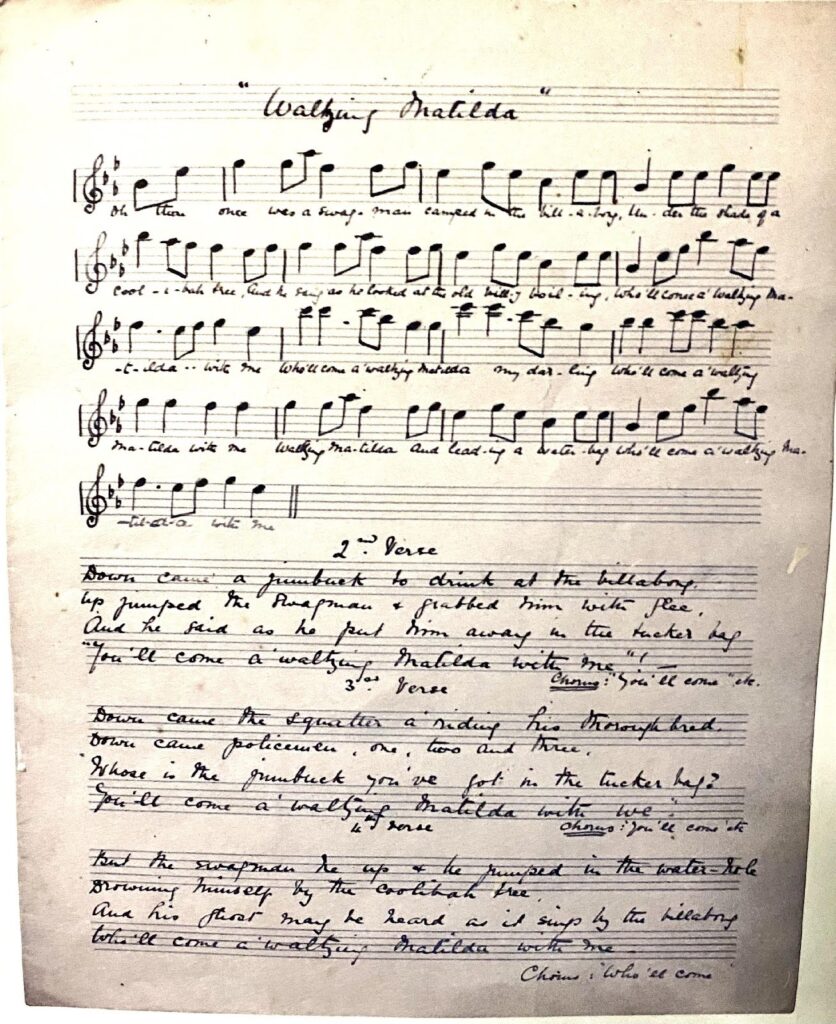

Waltzing Matilda

Returning from Dagworth Station to Sydney on 2 September 1894, Paterson read in ‘The Sydney Morning Herald’ that the Dagworth shearing shed had been burnt down the night before, with wool and 143 lambs.

The Dagworth fire brought on Queensland’s draconian “Peace Preservation Bill”. In Brisbane 15,000 protested, but democratic rights lapsed, police and magisterial powers increased, and bounties offered for “ratting on mates” and conviction of arsonists.

With Sarah Riley, his fiancé of eight years, Paterson returned to ‘Dagworth’ in January 1895 to help resolve the strike. One night, when the Overseer, Jack Carter came in to dinner late, after riding the run, MacPherson asked,

“Did you see any men today, Mr Carter?”

“Only a bagman, waltzing Matilda along the river”, replied Carter.

“What does waltzing Matilda mean?” asked Paterson, who had not heard the expression before.

“Matilda is an affectionate word for swag”, explained MacPherson. “His Matilda is a swagman’s travelling companion. He sleeps with her every night. Waltzing Matilda means walking with a swag. It’s the same as “humping the bluey” or “on the wallaby”.

Matilda goes back thousands of years to Hilde. In Norse myth Hilde was a goddess of war. Hilde later became Machilde, the mighty battle maiden, a female warrior, Valkyrie or Amazon, like Boadicea. Later still, the church claimed and canonised her as St Hilda.

Armies in Europe corrupted Mathilde to mean a camp follower, a wandering prostitute, or comfort woman. A soldier with no other warm body to keep him cosy at night slept in his great coat. Whimsically, the men called this comforter their ‘Mathilde’.

By day they carried their Mathilde in a roll on their back, like Australian swaggies humping the bluey still did, as I remember them after the war, in my childhood, around the outskirts of Melbourne; solitary grey unshaven men, sheltering under bridges.

In Europe, medieval journeymen and carpenters also carried backpacks, likewise called Mathilde as they walked from village to village, as it was said, “auf der walz Mathilde”. The German word walz meant walk. The waltz was initially the walking dance.

Europeans brought the phrase Waltzing Matilda to our gold fields in the 1850s. They followed Burke and Wills into western Queensland from Victoria and South Australia so the phrase was not known in New South Wales or by Paterson till that night at Dagworth.

Paterson and his fiancé Sarah stayed three weeks at Dagworth. They picnicked with Bob Macpherson and his sister Christine at Kynuna Billabong, under police guard, protecting also the nearby Cobb & Co coach exchange, while Macpherson briefed the lawyer:

“The night our shed burnt, police had a stockade like Eureka at Dagworth to protect Chinese scab shearers. From 1:00 am, the strikers distracted us squatters and jackaroos. We exchanged 40 rounds, while they set fire to the back of the shed, out of sight.”

Jolly Swagman

“The morning after the fire”, Mac Pherson explained to Paterson over their picnic lunch, “three police officers and I found a swagman dead by the Four Mile Billabong, nine miles upstream from Kynuna. He had union tickets in his pocket and a gunshot wound”.

Christened Samuel Augusta in Berlin in 1862, Hoffmeister was well known in the area as Frenchy for his Continental accent; as a rabble-rouser in 1891, an anarchist with a shingle loose. Always armed, Frenchy was thought to be involved in firing the ‘Dagworth’ shed.

After lunch Christine played on a zither the Scots’ tune “Craigielea”. She had heard a band play it at the Warnambool races the previous April. Paterson fitted the words of his “Waltzing Matilda” to her catchy tune, now one of the world’s top ten recorded songs.

Covert Allegory

First performed to children and like many other nursery rhymes, explained Magoffin, the song’s widespread popularity probably rests on Paterson’s concealed political allegory. As ever, the underdog is up against the unequal power of an overbearing establishment.

Like once upon a time, the phrase, there was once a swagman, signifies a ballad, relevant to all times. The jolly swagman is the disenfranchised and itinerant worker with only a Coolibah tree for shelter, waltzing his Matilda through the billabong country, to freedom.

Asking, “Who’ll come a’ waltzing Matilda with me?” the citizen swagman invites others to join the dancing freedom journey, towards a fair society, in this wide brown land, upholding a fair go for everyone.

Waiting till his billy boiled is code for the boiling social unrest, then flaring into arson. In ‘Freedom on the Wallaby’, Paterson’s mate Lawson had written, “ … she’ll knock the tyrants silly. She’s going to light another fire and boil another billy.”

Magoffin claims Dagworth was the last time Australians fired on each other, overlooking massacres and atrocities even into the nineteen sixties, with so called “boongs” still shot for sport in Durak country around the Ord River in the Northern Territory.

Jumbuck is Aboriginal for fleecy white cloud, the term which First Australians used when they first saw sheep. Paterson’s jumbuck, grabbed for the tucker bag, symbolises the ill-gotten wealth of the ruling class, rightfully reclaimed by the union, for the underclass.

“Up came the squatter mounted on his thoroughbred” of course signifies the ruling elite, represented by Bob Macpherson, who in later years often recounted that Paterson while composing the song had said to his host “We’ll put you on a thoroughbred Bob.”

“Up came troopers, one, two and three”, stresses the use of excessive power against a single swagman. The police saying, “You’ll come a’ waltzing Matilda with me” means the swaggie will join his comrades already in jail for offences during the strike.

The swaggie’s daylight suicide by drowning, in front of four competent authority figures portrays the abject failure of the union, but the ghostly “voice” of the underdog from the land of billabongs continues to haunt authority until unfair regimes are changed.

Using disguised allegory in the ancient tradition of ballad, jester or clown, Paterson avoided the trouble Lawson got into for his explicit dissent. By replacing protest with an affirmative freedom song, Banjo offers hope – to national and world-wide acclaim.

Writing this, camped in that very billabong, where our jolly swagman died, I find its clay floor dry, crazed by drought; no water (billa in Aboriginal) be that billa bong, meaning dead, stagnant, least of all dancing yet his ghost can be heard, whispering round my page.

Resolution

Only Mike Faye, the illiterate publican of the Blue Heeler had money. Carrying the town, squatters and 150 shearers alike, throughout the strikes, he probably paid Paterson also. It was the wet season. Wet sheep were dying from fly strike. All wanted the strife settled.

During his three weeks at Dagworth, Paterson, in the background was secretly brokering a deal between squatters and shearers. With co-operation from Police Magistrate Ernest Eglinton, Paterson persuaded him to withdraw all serious charges.

Forgoing his ₤1,000 government reward, Squatter Macpherson refused to give evidence against John Tierney, on trial for the Dagworth Outrage. Instead, Bob shouted the shearers who’d burnt his shed. Publican Fahey had Champagne already cooling under wet bags.

Instead of shooting each other, squatters and shearers together in the Kynuna Hotel sang our dear silly song, Waltzing Matilda, baffling to most, even today. The shearers returned to work. Dagworth sheep were shorn, banks repaid, and everyone shut up for forty years.

The Coroner found swaggie Hoffmeister died by suicide, but as punishment was dire, it is possible his comrades shot him so he couldn’t blab about the armed attack on Dagworth, mounted from their camp at this very billabong where Frenchy “was picked up dead”.

Sarah ended her engagement to Paterson, not over any affair with Christine, as some say, but over the bore water, which Banjo joked was the secret of his song, and of which Bob splashed but little, given its aroma, into the copious rum of their heavy drinking sessions.

By 1906 Dagworth was again bankrupt. Owing ₤101,000, Bob Macpherson died soon after in a drinking school at the pub, since restored by RM Williams and renamed The Blue Healer, where the jolly swagman Frenchy Hoffmeister also, enjoyed his last glass

Later Paterson

Norman Lindsay said Paterson was wherever the action was. As Foreign Correspondent for the “Sydney Morning Herald” he rode with The Light Horse in the Boer War. He interviewed Kitchener, Churchill and Kipling, with whom he remained friends.

Arriving at Bloemfontein on horseback before the troops, Paterson with a few other journalists liberated the capital. In 1901 he sailed to China to cover the Boxer Rebellion but arrived in Shanghai after the fighting ended.

In the First World War Banjo served with horses as an ambulance driver, rising to the rank of Major. He married Alice Walker from Tenterfield, a niece of Governor King of New South Wales. His friend Lawson married the niece of Labor Premier Jack Lang.

Retiring by nature Banjo was surprised by fame when crowds on Circular Quay, fare-welling Diggers embarking for WWI, spontaneously sang Waltzing Matilda, but with legal caution he deferred owning authorship of the ballad till close to his death in 1941.

John Wilson

August 2003